Promotion

Use code MOM24 for 20% off site wide + free shipping over $45

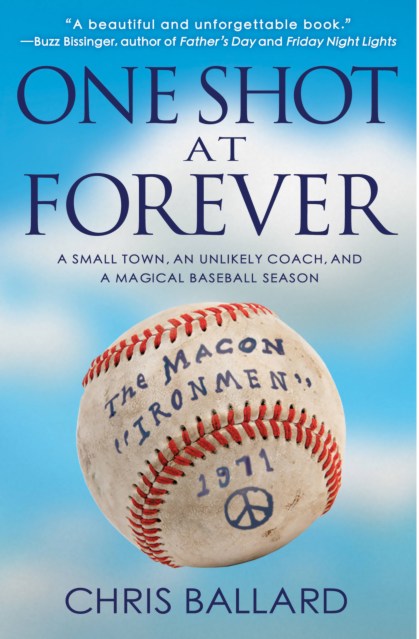

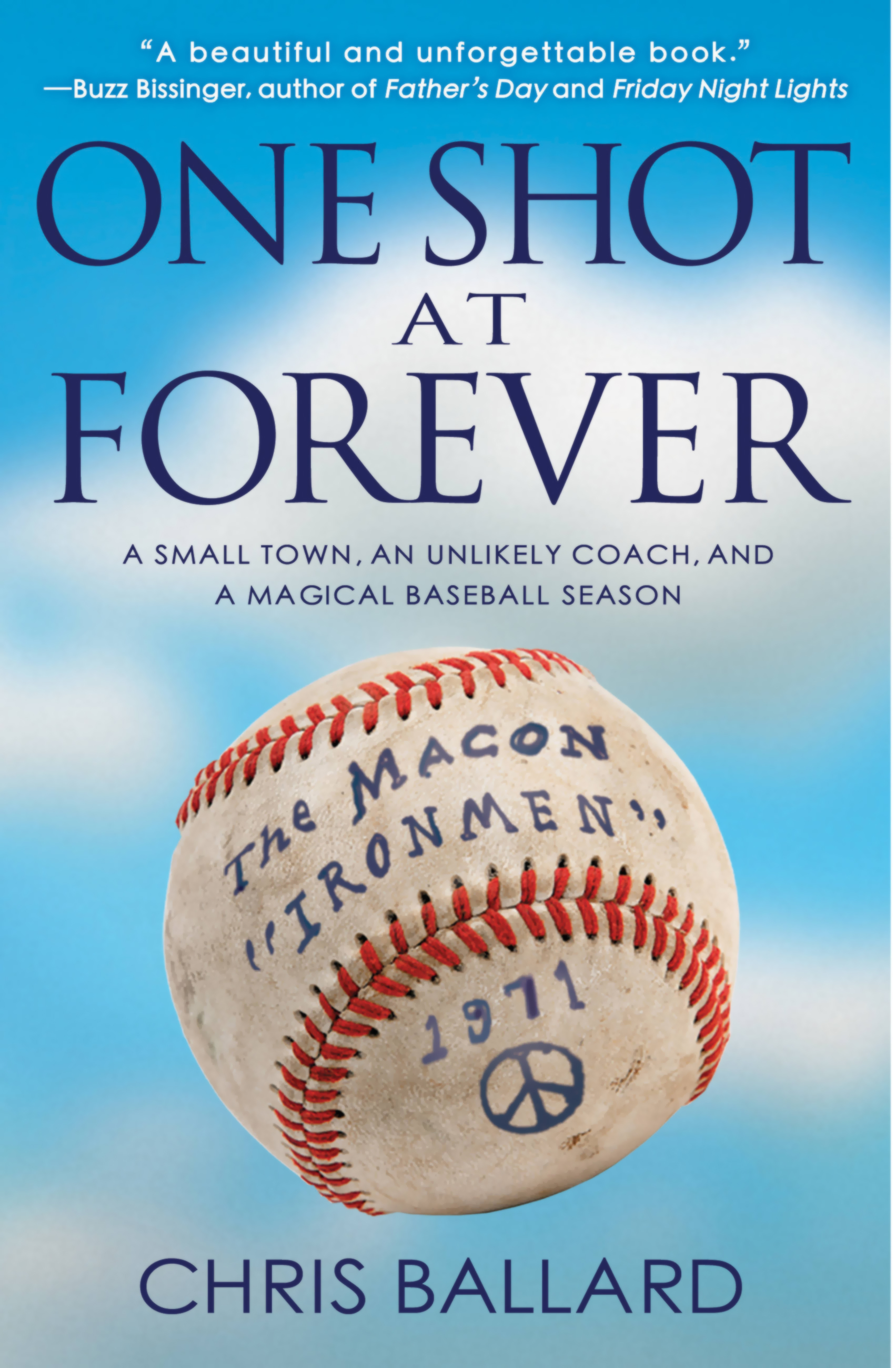

One Shot at Forever

A Small Town, an Unlikely Coach, and a Magical Baseball Season

Contributors

Formats and Prices

Price

$9.99Price

$12.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $9.99 $12.99 CAD

- Trade Paperback $21.99 $28.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around May 15, 2012. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

In 1971, a small-town high school baseball team from rural Illinois, playing with hand-me-down uniforms and peace signs on their hats, defied convention and the odds. Led by an English teacher with no coaching experience, the Macon Ironmen emerged from a field of 370 teams to represent the smallest school in Illinois history to make the state final, a distinction that still stands. There the Ironmen would play against a Chicago powerhouse in a dramatic game that would change their lives forever.

In this gripping, cinematic narrative, Chris Ballard tells the story of the team and its coach, Lynn Sweet: a hippie, dreamer, and intellectual who arrived in Macon in 1966, bringing progressive ideas to a town stuck in the Eisenhower era. Beloved by students but not administration, Sweet reluctantly took over the ragtag team, intent on teaching the boys as much about life as baseball. Together they embarked on an improbable postseason run that buoyed a small town in desperate need of something to celebrate.

Engaging and poignant, One Shot at Forever is a testament to the power of high school sports to shape the lives of those who play them, and it reminds us that there are few bonds more sacred than that among a coach, a team, and a town.

“Macon’s run at the title reminds us why sports matter and why sportswriting has such great power to inspire. . . [It’s] one hell of a good story, and Ballard has written one hell of a good book.” — Jonathan Eig, Chicago Tribune

Genre:

- On Sale

- May 15, 2012

- Page Count

- 272 pages

- Publisher

- Hachette Books

- ISBN-13

- 9781401304324

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use