Promotion

Use code MOM24 for 20% off site wide + free shipping over $45

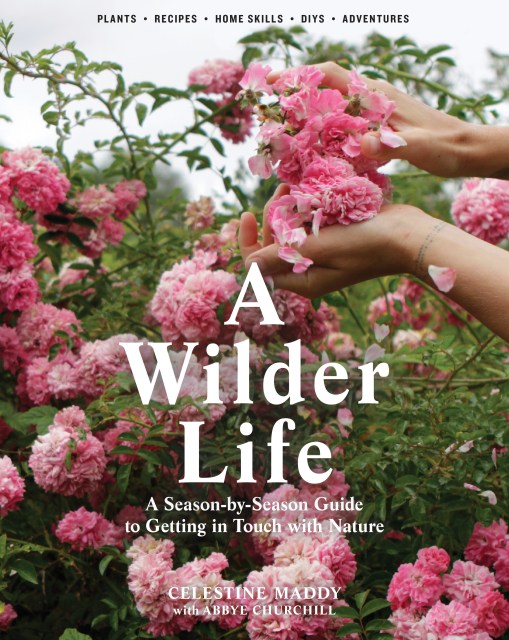

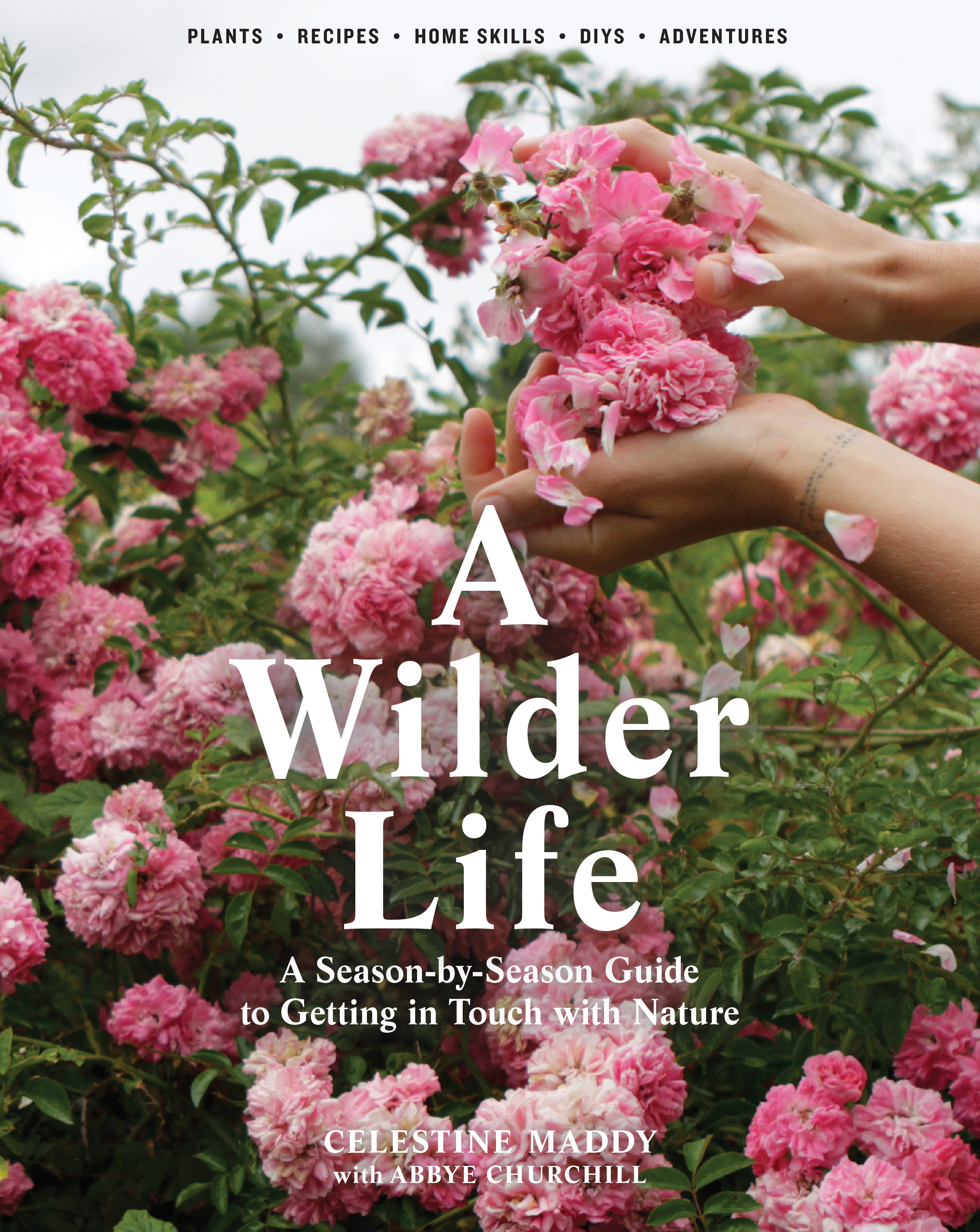

A Wilder Life

A Season-by-Season Guide to Getting in Touch with Nature

Contributors

By Abbye Churchill

Formats and Prices

Price

$29.95Price

$37.95 CADFormat

Format:

- Trade Paperback $29.95 $37.95 CAD

- ebook $14.99 $19.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around January 26, 2016. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

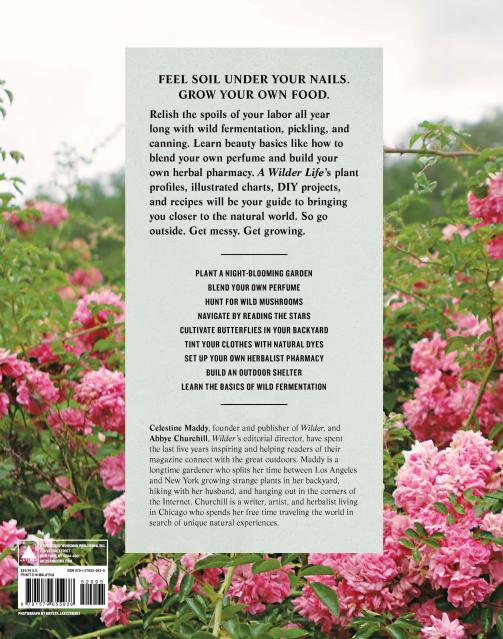

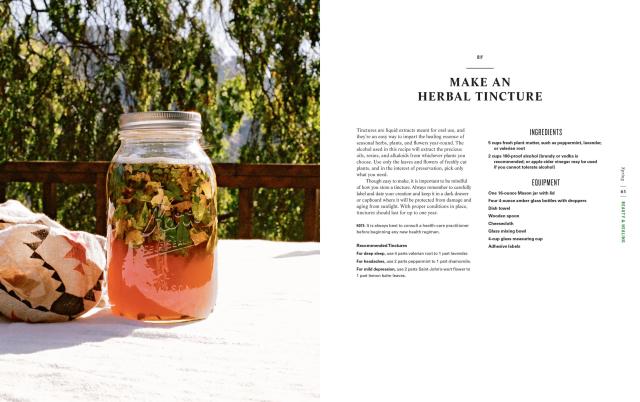

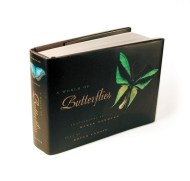

In our technology-driven, workaday world, connecting with nature has never before been more essential. A Wilder Life, a beautiful oversized lifestyle book by the team behind the popular Wilder Quarterly, gives readers indispensable ideas for interacting with the great outdoors. Learn to plant a night-blooming garden, navigate by reading the stars, build an outdoor shelter, make dry shampoo, identify insects, cultivate butterflies in a backyard, or tint your clothes with natural dyes. Like a modern-day Whole Earth Catalog, A Wilder Life gives us DIY projects and old-world skills that are being reclaimed by a new generation. Divided into sections pertaining to each season and covering self-reliance, growing and gardening, cooking, health and beauty, and wilderness, and with photos and illustrations evocative of the great outdoors, A Wilder Life shows that getting in touch with nature is possible no matter who you are and—more important—where you are.

Genre:

-

“The new book that’s becoming our natural beauty obsession. . . . It’s a comprehensive, coffee table–worthy, DIY project–packed manual for enjoying all four seasons through interaction with nature—including recipes (foraged elderflower champagne! Pumpkin butter!), gardening and home tips. . . . It’s also a particularly good resource for natural-beauty buffs.”

—Vogue.com

“Wander through the pages of A Wilder Life in awe and appreciation. . . . [The book] urges readers to garden with a purpose—to stew, brew, can and pot. . . . . Nature isn’t just a screen saver. It’s a soul saver.”

—The New York Times Book Review

“Will smarten up any side table.”

—Domino

“A beautiful, informative, thoughtful compilation of facts, recipes, DIY instructions, and more—a book designed to put you a little more in touch with nature and a lot more in touch with yourself.”

—Organic Lifestyle Magazine

- On Sale

- Jan 26, 2016

- Page Count

- 272 pages

- Publisher

- Artisan

- ISBN-13

- 9781579655938

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use