Promotion

Use code MOM24 for 20% off site wide + free shipping over $45

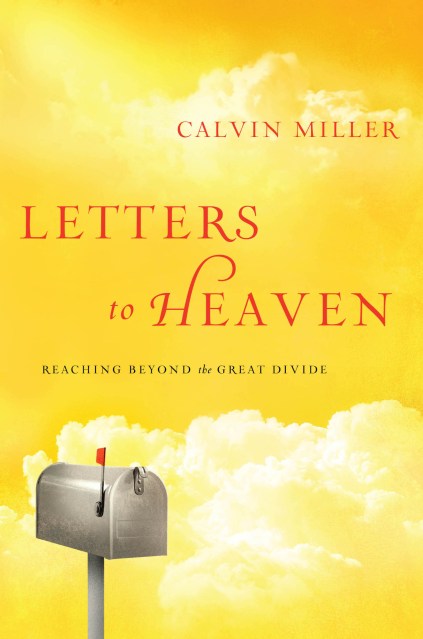

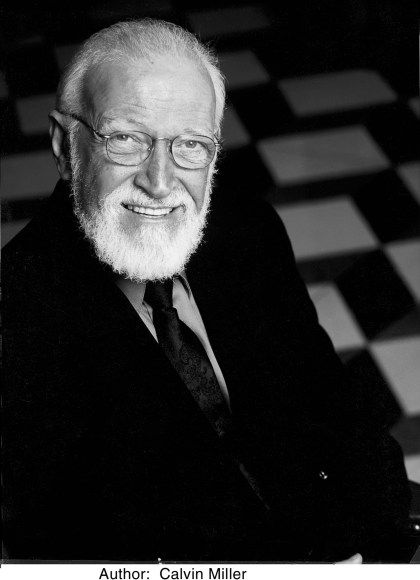

Letters to Heaven

Reaching Beyond the Great Divide

Contributors

Formats and Prices

Price

$9.99Price

$12.99 CADFormat

Format:

ebook $9.99 $12.99 CADThis item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around February 1, 2012. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

In these masterfully written letters to heaven, Calvin Miller thanks, lovingly reflects on-and sometimes confesses his regrets to -the departed influences in his life. Some are names familiar to us all (C. S. Lewis, Todd Beamer, Oscar Wilde); others he knew well; and some he only admired from a distance. But all brought a brightness to his life or challenged him to live more fully in some way. Aware that eternity for any of us is only a step away, Miller has sought to complete the unfinished business of life by writing letters to the great beyond. This moving work will not only elicit a desire in readers to reconcile all things unfinished, but teach the living about the importance of people and the treasure of faith while holding out for us all the hope that awaits..

Genre:

- On Sale

- Feb 1, 2012

- Page Count

- 224 pages

- Publisher

- Worthy Books

- ISBN-13

- 9781617950476

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use