Promotion

Use code MOM24 for 20% off site wide + free shipping over $45

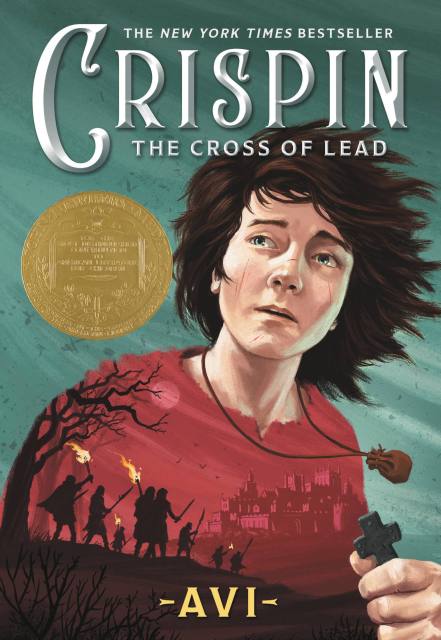

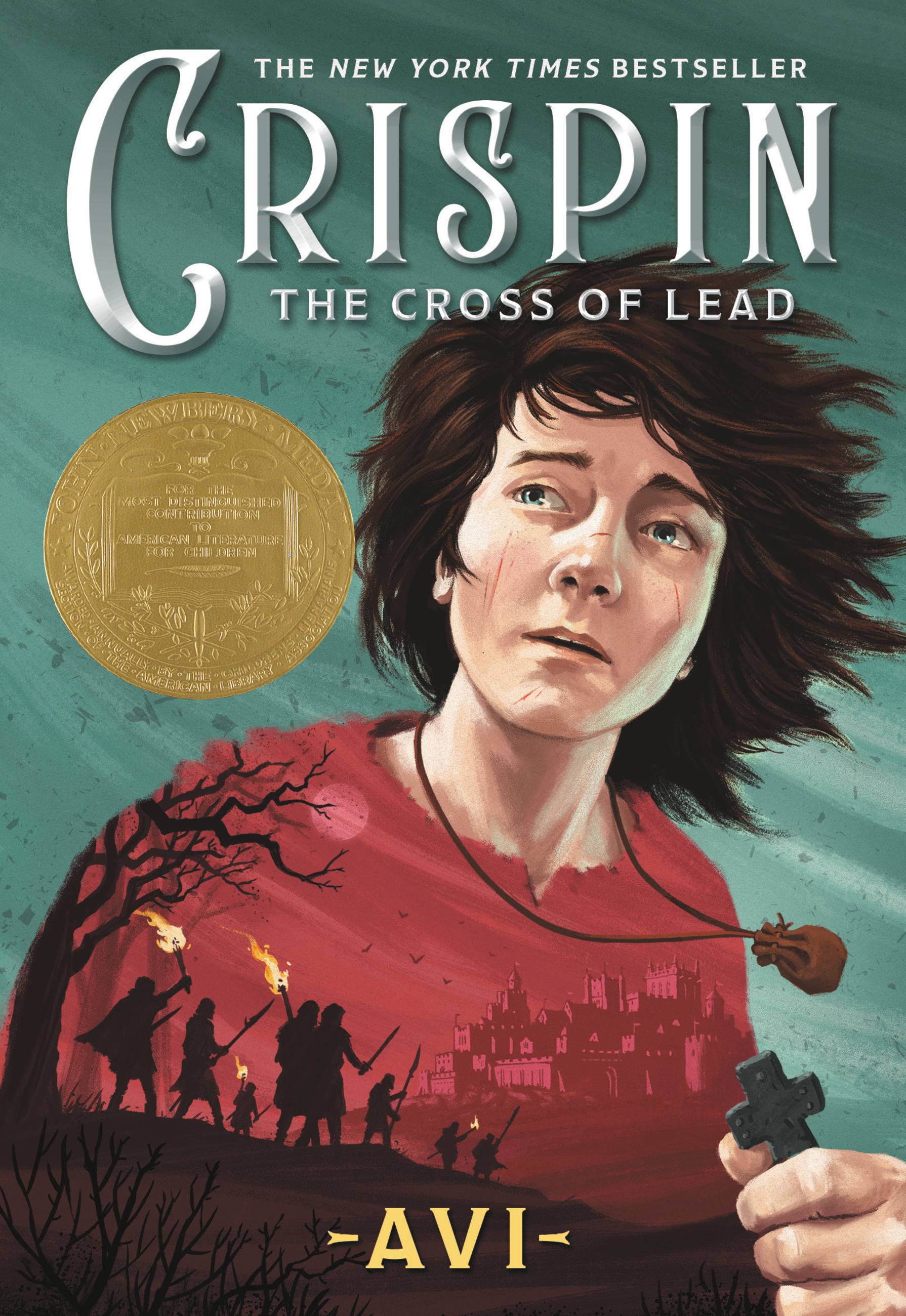

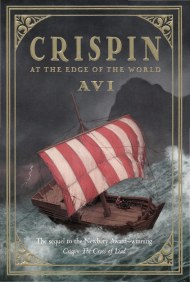

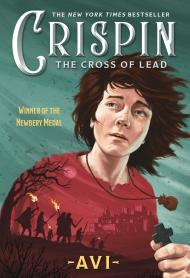

Crispin: The Cross of Lead (Newbery Medal Winner)

Contributors

By Avi

Formats and Prices

Price

$7.99Price

$9.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $7.99 $9.99 CAD

- Hardcover $17.99 $22.99 CAD

- Trade Paperback $8.99 $12.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around July 25, 2010. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

Sometimes I ran, sometimes all I could do was walk. All I knew was that if the steward overtook me, I’d not survive for long….

Crispin is a poor thirteen-year-old peasant in medieval England. Accused of a crime he did not commit, he has been declared a "wolf’s head," meaning he may be killed on sight, by anyone. He flees his tiny village with nothing but his mother’s cross of lead.

In the English countryside, Crispin meets a man named Bear, who forces Crispin to become his servant yet encourages him to think for himself. But as Crispin’s enemies draw ever closer, he is pulled right into the fortress of his foes, where he must find a way to save their very lives.

A master of breathtaking plot twists and vivid characters, award-winning author Avi brings the full force of his storytelling powers to the world of medieval England.

Genre:

-

* "Avi's plot is engineered for maximum thrills, with twists, turns, and treachery aplenty.... A page-turner to delight Avi's fans, it will leave readers hoping for a sequel."Publishers Weekly, starred review

-

* "The book is a page-turner from beginning to end.... [A] meticulously crafted story, full of adventure, mystery, and action."School Library Journal, starred review

-

"Historical fiction at its finest."Voice of Youth Advocates

- On Sale

- Jul 25, 2010

- Page Count

- 320 pages

- Publisher

- Little, Brown Books for Young Readers

- ISBN-13

- 9781423140719

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use