Promotion

Use code MOM24 for 20% off site wide + free shipping over $45

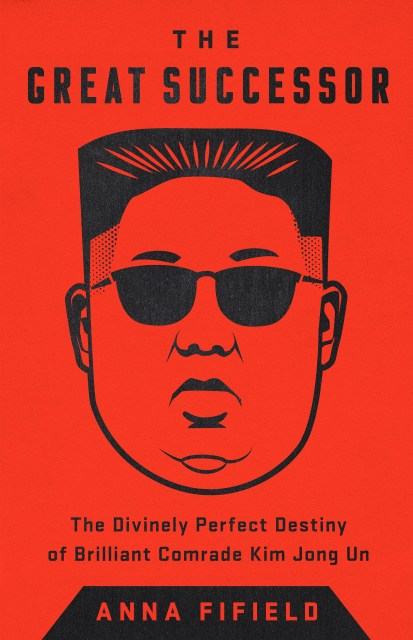

The Great Successor

The Divinely Perfect Destiny of Brilliant Comrade Kim Jong Un

Contributors

By Anna Fifield

Formats and Prices

Price

$28.00Price

$36.50 CADFormat

Format:

- Hardcover $28.00 $36.50 CAD

- ebook $12.99 $16.99 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged)

- Trade Paperback $17.99 $22.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around June 11, 2019. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

The behind-the-scenes story of the rise and reign of the world’s strangest and most elusive tyrant, Kim Jong Un, by the journalist with the best connections and insights into the bizarrely dangerous world of North Korea.

Since his birth in 1984, Kim Jong Un has been swaddled in myth and propaganda, from the plainly silly — he could supposedly drive a car at the age of three — to the grimly bloody stories of family members who perished at his command.

Anna Fifield reconstructs Kim’s past and present with exclusive access to sources near him and brings her unique understanding to explain the dynastic mission of the Kim family in North Korea. The archaic notion of despotic family rule matches the almost medieval hardship the country has suffered under the Kims. Few people thought that a young, untested, unhealthy, Swiss-educated basketball fanatic could hold together a country that should have fallen apart years ago. But Kim Jong Un has not just survived, he has thrived, abetted by the approval of Donald Trump and diplomacy’s weirdest bromance.

Skeptical yet insightful, Fifield creates a captivating portrait of the oddest and most secretive political regime in the world — one that is isolated yet internationally relevant, bankrupt yet in possession of nuclear weapons — and its ruler, the self-proclaimed Beloved and Respected Leader, Kim Jong Un.

Genre:

- On Sale

- Jun 11, 2019

- Page Count

- 336 pages

- Publisher

- PublicAffairs

- ISBN-13

- 9781541742482

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use