Promotion

Use code MOM24 for 20% off site wide + free shipping over $45

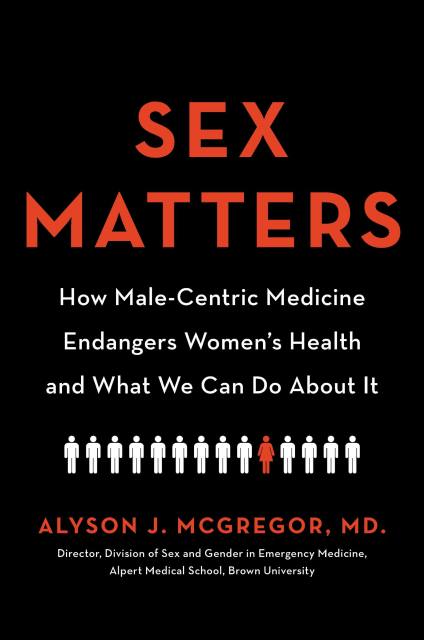

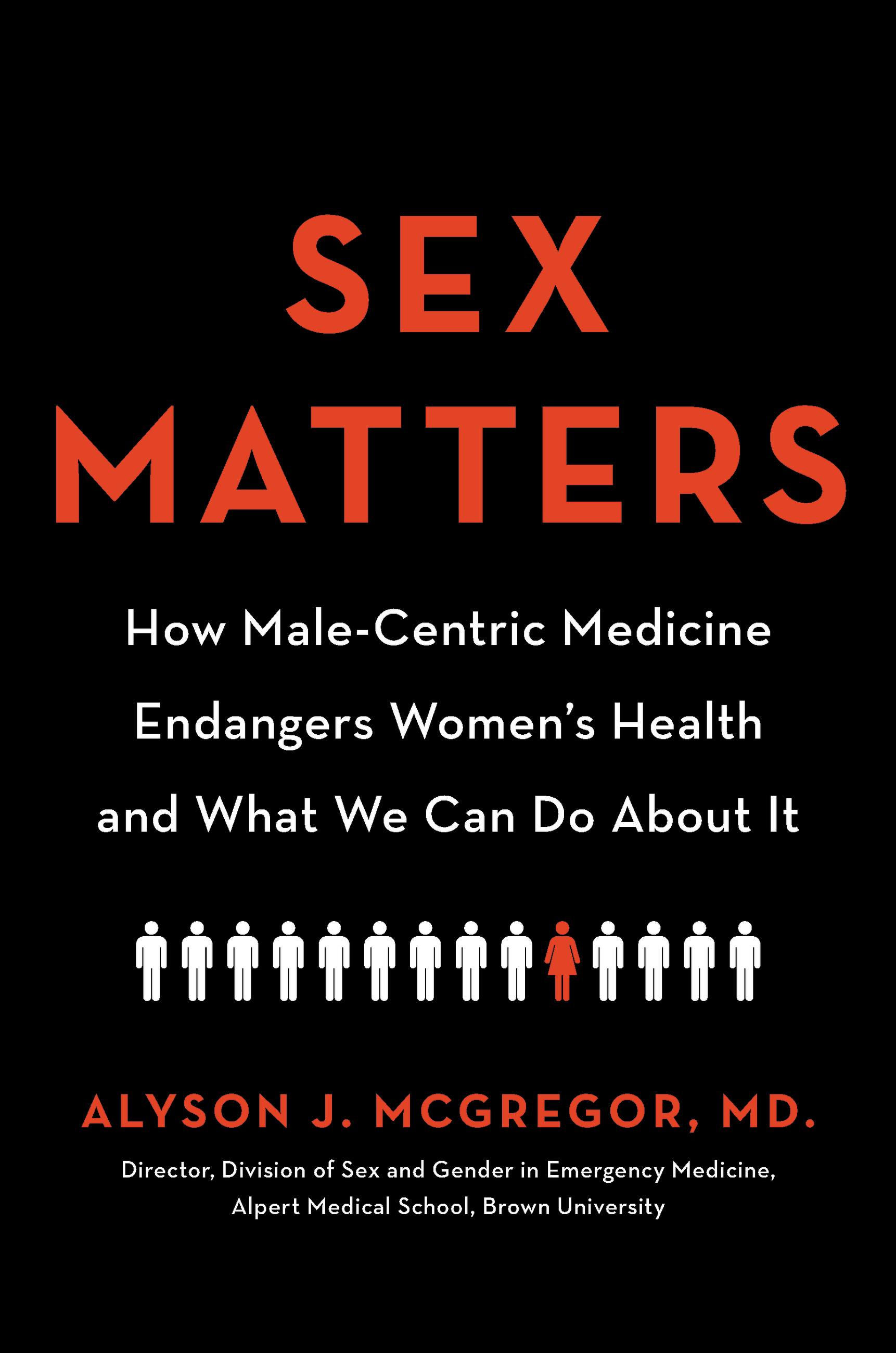

Sex Matters

How Male-Centric Medicine Endangers Women's Health and What We Can Do About It

Contributors

Formats and Prices

Price

$14.99Price

$19.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $14.99 $19.99 CAD

- Hardcover $28.00 $35.00 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged)

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around May 19, 2020. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

Get the right care for your body — and avoid treatments that can endanger women — with this important manual from a physician who is a leading expert on sex and gender medicine.

Sex Matters tackles one of the most urgent, yet unspoken issues facing women’s health care today: all models of medical research and practice are based on male-centric models that ignore the unique biological and emotional differences between men and women — an omission that can endanger women’s lives.

The facts surrounding how male-centric medicine impacts women’s health every day are chilling: in the ER, women are more likely to receive a psychiatric diagnosis with regard to opioid use, while men are more likely to be referred for detoxification; the more vocal women become about their pain, the more likely their providers are to prescribe either inadequate or inappropriate pain relief medication; women often present with nontraditional symptoms of stroke, which causes delays in recognition by both them and their health professionals; and a government accountability study found that 80% of drugs that are withdrawn from the market are due to side effects that happen to women (a result of testing drugs mostly on men).

Leading expert on sex and gender medicine Dr. Alyson McGregor focuses on the key areas where these differences are most potentially harmful, addressing:

- Cardiac and stroke diagnosis and treatment in women

- Prescription and dosing of pharmaceuticals;

- Subjective evaluation of women’s symptoms;

- Pain and pain management;

- Hormones and female biochemistry (including prescribed hormones);

- How economic status, race, and gender identity are additional critical factors.

Not only does Dr. McGregor explore these disparities in depth, she shares clear, practical suggestions for what women can do to protect themselves. A work of riveting exposé with revelatory insights and actionable guidance for navigating the medical establishment, Sex Matters is an empowering roadmap for reinventing modern medicine — and for self-care.

Genre:

- On Sale

- May 19, 2020

- Page Count

- 272 pages

- Publisher

- Hachette Go

- ISBN-13

- 9780738246758

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use