Promotion

Use code MOM24 for 20% off site wide + free shipping over $45

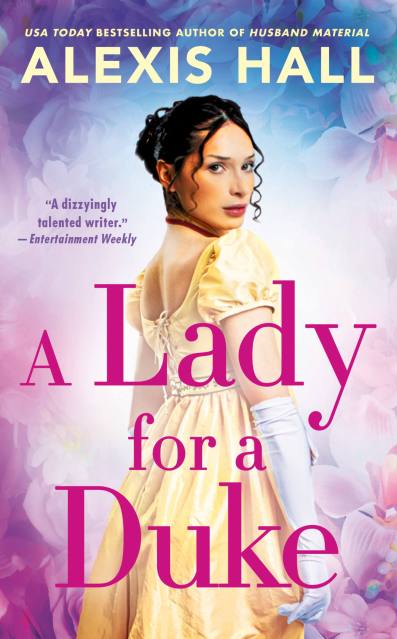

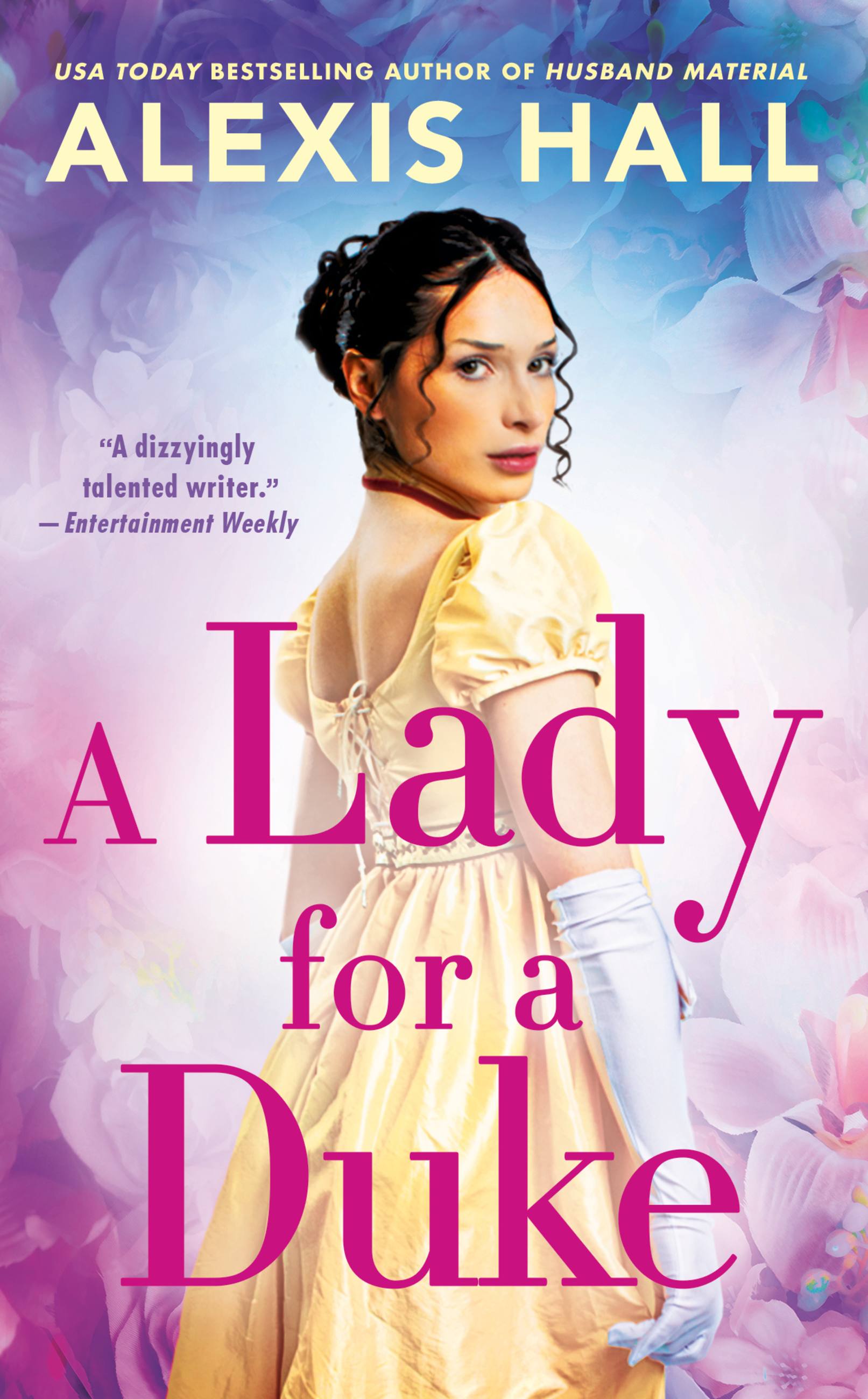

A Lady for a Duke

Contributors

By Alexis Hall

Formats and Prices

Price

$8.99Price

$12.99 CADFormat

Format:

- Mass Market $8.99 $12.99 CAD

- ebook $7.99 $9.99 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged) $31.99

- Trade Paperback $17.99 $23.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around June 6, 2023. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

When Viola Carroll was presumed dead at Waterloo she took the opportunity to live, at last, as herself. But freedom does not come without a price, and Viola paid for hers with the loss of her wealth, her title, and her closest companion, Justin de Vere, the Duke of Gracewood.

Only when their families reconnect, years after the war, does Viola learn how deep that loss truly was. Shattered without her, Gracewood has retreated so far into grief that Viola barely recognises her old friend in the lonely, brooding man he has become.

As Viola strives to bring Gracewood back to himself, fresh desires give new names to old feelings. Feelings that would have been impossible once and may be impossible still, but which Viola cannot deny. Even if they cost her everything, all over again.

Only when their families reconnect, years after the war, does Viola learn how deep that loss truly was. Shattered without her, Gracewood has retreated so far into grief that Viola barely recognises her old friend in the lonely, brooding man he has become.

As Viola strives to bring Gracewood back to himself, fresh desires give new names to old feelings. Feelings that would have been impossible once and may be impossible still, but which Viola cannot deny. Even if they cost her everything, all over again.

Genre:

-

“Hall has hit it out of the park with this emotionally resonant, character-driven Regency romance . . . [a] nuanced, swoony and a stellar example of what romance can do.”BookPage, Starred Review

-

"Hall is a consistently beautiful writer, but this story, the first in a new series, may be his best yet.”Kirkus, Starred Review

-

“Hall has a gift for humor but is also skilled at composing passages that evoke the deepest emotions, whether the ache of long-denied love, crushing grief or the relief and soulful joy of being accepted and adored as one's most authentic self.”Library Journal, Starred Review

-

"The period banter is unparalleled as Hall pulls his characters out of the drawing room and into far closer quarters. He explores difficult subjects with a sharpness matched only by the tenderness underpinning the relationship between Viola and Gracewood. Fans of Lisa Kleypas and anyone looking for romance centering trans characters owe it to themselves to check this out."Publishers Weekly, Starred Review

-

“Hall has a gift for humor but is also skilled at composing passages that evoke the deepest emotions, whether the ache of long-denied love, crushing grief or the relief and soulful joy of being accepted and adored as one's most authentic self.”Shelf Awareness, Starred Review

-

“His beautiful and moving first historical romance, which has just enough humor to lighten the angst, may be the sweetest book of this summer.”NPR

-

“Alexis Hall was made for writing these period narratives. . . . Featuring Hall’s trademark wit, a second chance romance infused with grief, yearning and acceptance, A Lady for a Duke is a vivid, moving tale.”The Nerd Daily

-

“A name to follow in romance. . . . With A Lady for a Duke, Hall cements himself even further as a writer who pushes the genre beyond its previous borders and helps to reestablish a new definition altogether.”Paste Magazine

-

“If you're looking to swoon, laugh, and cry, then this is the audiobook for you.”Buzzfeed

-

"Hall is a dizzyingly talented writer, one likely to spur envy in anyone who's ever picked up a pen."Entertainment Weekly

-

"Simply the best writer I've come across in years."Laura Kinsale, New York Times bestselling author of Flowers from the Storm

- On Sale

- Jun 6, 2023

- Page Count

- 480 pages

- Publisher

- Forever

- ISBN-13

- 9781538753767

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use