Promotion

Use code MOM24 for 20% off site wide + free shipping over $45

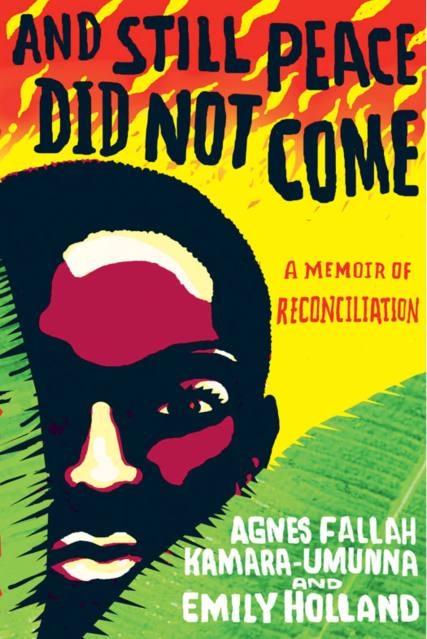

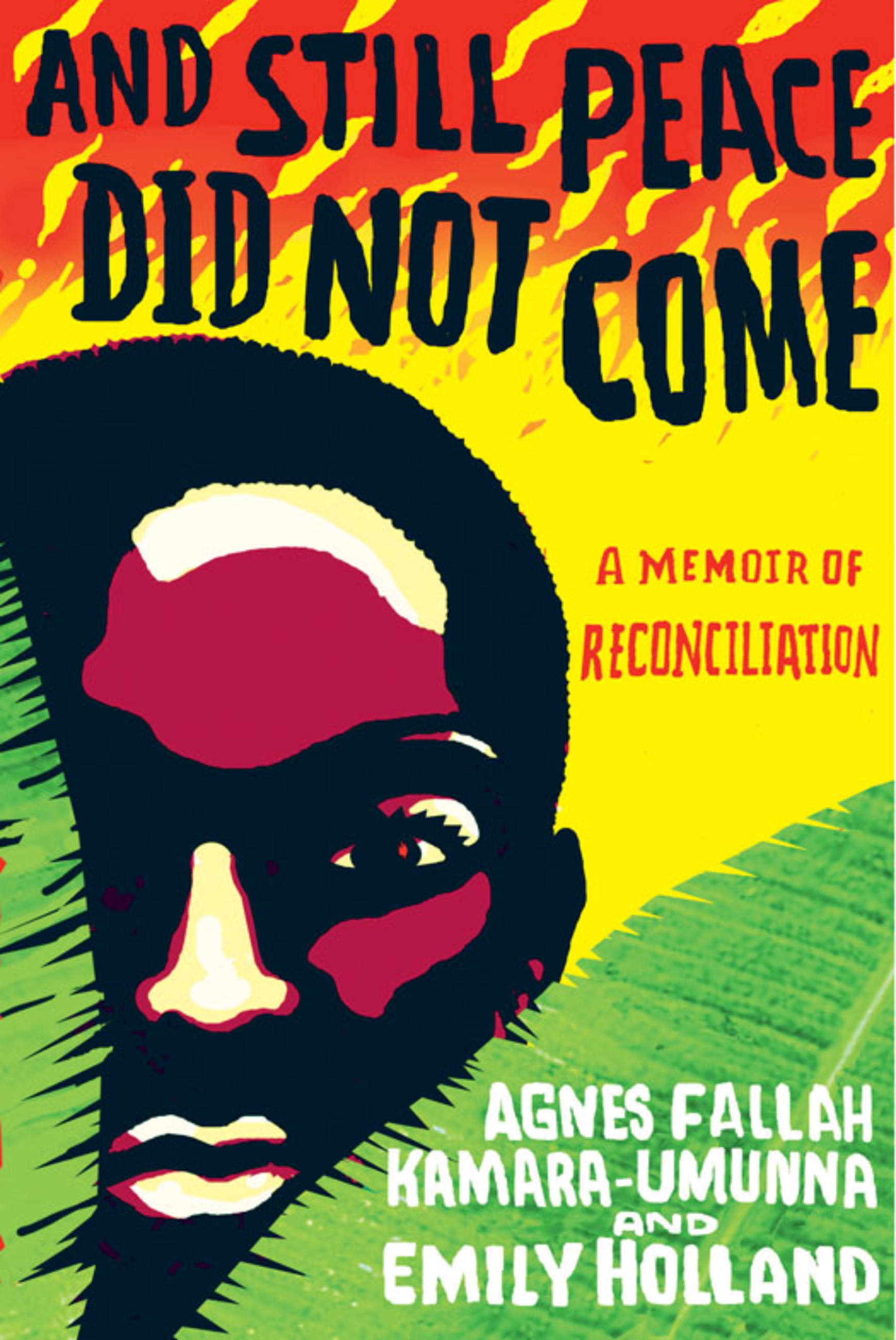

And Still Peace Did Not Come

A Memoir of Reconciliation

Contributors

Formats and Prices

Price

$10.99Price

$13.99 CADFormat

Format:

ebook $10.99 $13.99 CADThis item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around March 22, 2011. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

Slowly, they made their way to the safety of Sierra Leone. They were the lucky ones.

After years of exile, with the fighting seemingly over, Agnes returned to Liberia–a country now devastated by years of civil war. Families have been torn apart, villages destroyed, and it seems as though no one has been spared. Reeling, and unsure of what to do in this place so different from the home of her memories, Agnes accepted a job at the local UN-run radio station. Their mission is peace and their method is reconciliation through understanding and communication. Soon, she came up with a daring plan: Find the former child soldiers, and record their stories. And so Agnes, then a 43-year-old single mother of four, headed out to the ghettos of Monrovia and befriended them, drinking Club Beer and smoking Dunhill cigarettes with them, earning their trust. One by one, they spoke on her program, Straight from the Heart, and slowly, it seemed like reconciliation and forgiveness might be possible.

From Ellen Johnson-Sirleaf, Africa’s first female president, to Butt Naked, a warlord whose horrific story is as unforgettable as his nickname–everyone has a story to tell. Victims and perpetrators. Boys and girls, mothers and fathers. Agnes comforts rape survivors, elicits testimonials from warlords, and is targeted with death threats–all live on the air.

Set in a place where monkeys, not raccoons, are the scourge of homeowners; the trees have roots like elephant legs; and peacebuilding is happening from the ground-up. Harrowing, bleak, hopeful, humorous, and deeply moving–And Still Peace Did Not Come is not only Agnes’s memoir: It is also her testimony to a nation’s descent into the horrors of civil war, and its subsequent rise out of the ashes.

Genre:

- On Sale

- Mar 22, 2011

- Page Count

- 256 pages

- Publisher

- Hachette Books

- ISBN-13

- 9781401396602

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use