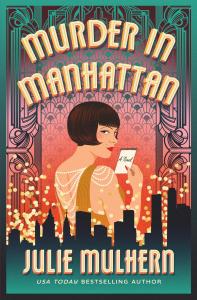

The Fashion Critic Flapper: The 20s Reporter that Inspired Murder in Manhattan

In the glittering party that was 1920s Manhattan, when an estimated 30,000 speakeasies flourished behind unmarked doors and jazz pulsed through smoke-filled rooms until dawn, one young woman made it her business to chronicle it all. Lois Long, writing under the pseudonym “Lipstick,” became The New Yorker’s eyes and ears, transforming gossip and fashion into an art form while living the reckless, exhilarating life she documented.

Hired by The New Yorker in 1925, just months after the magazine’s founding, Long’s job was a flapper’s dream: go out every night, hit the hottest clubs, and report back. Long threw herself into the role with abandon, often staying out until 4:00 or 5:00 a.m. Then, with the scent of bootleg gin lingering on her gown, she’d stumble into the office to pound out her column before the deadline.

“Lipstick” quickly became essential reading for anyone in the know. Or anyone who wanted to be. Long wrote with wit, humor, and a sharp eye for both the absurd and the sublime. She reviewed nightclubs, speakeasies, and cabarets with the same critical rigor others applied to symphonies and opera. Her prose sparkled with insider knowledge and genuine enthusiasm, peppered with slang and knowing winks.

Long also revolutionized fashion criticism, writing about bateau necklines and beading with the same perceptive, irreverent approach she brought to speakeasies. In the 1920s, women’s fashion was undergoing a seismic shift. Hemlines had climbed to the knee (scandalous!), corsets had been tossed aside, and the new silhouette was boyishly straight as well as liberating. The flapper uniform—short skirts, dropped waists, cloche hats pulled low, and strings of paste pearls—wasn’t just a look; it was a declaration of independence.

Long had pressed her hand to her heart and pledged allegiance to practical, modern fashion that was still stylish. She wrote about clothes the way she wrote about clubs, with wit, accessibility, and zero patience for pretension. She understood the new American woman needed garments for her new life—one that involved dancing until dawn, working in offices, riding in automobiles, and moving through the world with unprecedented freedom. A dress that required a lady’s maid to fasten was useless to a girl who needed to dash from the office to the Cotton Club.

Long wasn’t merely an observer—she was an enthusiastic participant in the Jazz Age’s excesses. She dressed beautifully, drank heavily (Prohibition be damned), smoked constantly, and embodied the flapper ideal she helped popularize through her writing. Stories of her exploits became legendary around The New Yorker offices for arriving at work still in her evening gown, nursing hangovers with more cocktails, and treating the magazine’s premises as an extension of the nightlife she covered. She reportedly kept bootleg gin in her desk drawer and catnapped on the chaise in her office.

Long inspired Freddie Archer, the heroine in Murder in Manhattan. I wondered how a smart, curious woman with a sharp eye and access to every speakeasy, club, and cabaret in the five boroughs would react to murder. Turns out she orders a second (or third) martini while wearing a fabulous frock, carefully observes her surroundings, and dives right in. Just as Long might have done.

Discover the Book

This writer just found her next scoop . . . and it’s deadly. New York, 1925 – Freddie Archer frequents speakeasies and wild parties with her friends Dorothy Parker and Tallulah Bankhead. And the best part is that it’s all in a day’s work. Freddie loves her job writing the nightlife column for Gotham Magazine.

But Freddie’s latest piece just won her a bit more attention than she bargained for—from the police. A man mentioned in her column has been murdered. And Freddie is asked to keep an eye out for his fashionable female dinner companion. She’s told in no uncertain terms to stay out of the case herself.

So naturally, Freddie throws herself into an investigation that takes her from the elegant stores that line Fifth Avenue to the tenements south of Houston Street. Now between sipping gin rickeys with Scott and Zelda Fitzgerald and casting Broadway shows with Groucho Marx, she’s dodging bullets and dating a potentially dangerous bootlegger.