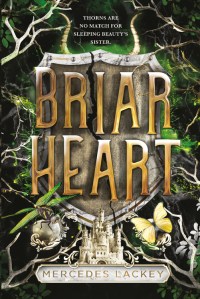

Mercedes Lackey on BRIARHEART

The Twice-told Tale

It’s no secret to anyone that I love retelling fairy tales. So do lots of other writers, as far as that goes; there are probably more versions of Beauty and the Beast than anyone could ever get around to reading and watching in a lifetime, for instance, and they run the gamut from experimental science fiction to outright pornography, and anything in between. I’ve written a lot of retold fairy tales, and some multiple versions of the same story for that matter, and I think there are several reasons why I keep coming back to that particular well of inspiration.

But for me, the most important reason is that fairy tales are very much what Dorothy L. Sayers termed moral fiction. By this, she didn’t mean “fiction with a moral,” although fairy tales have morals more often than not. She meant that stories she referred to as moral fiction were stories in which the good were sometimes rewarded, but the bad were always found out, their villainy exposed, and they were delivered to their punishment, which is certainly not the case in the real world. There may not be an unmitigated happy ending—if you’ve read real fairy tales and not the watered-down and prettified versions, you know the “happy ending” of marriage and happily-ever-after isn’t guaranteed. The Little Mermaid dies and is turned into sea-foam (while her beloved prince cavorts at his wedding with his chosen human bride). Tom Thumb gets into a fight with a poisonous spider and dies of the bite. One of the Twa Sisters drowns the other to get her betrothed, and the victim’s body parts are made into a harp. But the villains of the piece always get what they deserve, and oftentimes receive retribution in a form that the Supreme Court would surely judge as “cruel and unusual punishment.”

Sayers said at the time that mysteries were the only “moral fiction” left; had it been pointed out to her, I think she’d agree that fairy tales came under that heading as well.

Like Sayers, I prefer writing “moral fiction.” Not because moral fiction is escapist or unrealistic, but because even when the real world is full of injustice and unfairness, moral fiction gives the reader something to aspire to. As G.K. Chesterton once said, “Fairy tales do not tell children that dragons exist. Children already know that dragons exist. Fairy tales tell children that dragons can be killed.” In a harsh and unfair world, moral fiction, like fairy tales, reminds us that just because things are bad now, it doesn’t follow that you should give up and stop fighting for them to become better. The dragons can be killed. There can be a happy ending. It might not be your happy ending, but it will be a happy ending for someone. And that is the unselfish choice, all the more noble because it’s made in the full knowledge that though you kill the dragon, you aren’t going to be the one who wins the princess.

It was that unselfish choice that led me to create the heroine of Briarheart. Miri, though the daughter of a queen, is not a princess. She’s learned the lesson of the unselfish choice herself very early, since her father was killed trying to save someone else. She is, in fairy-tale fashion, endowed with a plethora of gifts both tangible and intangible—a lifestyle at the top of the pyramid, a stepfather who wants her to be both happy and fulfilled, and not one but two kinds of magic. But she’s not the princess, and she’s as burdened with duties as she is endowed with gifts. What if Sleeping Beauty had a sister? I asked myself, since one of the most fun things about retelling fairy tales is changing the narrative and seeing what comes of it. What if she had a sister who was protective and brave and was not going to stand there and watch some evil fairy queen destroy her darling baby sister?

Well, that sister—Miriam—was obviously going to need a posse. And she was going to need mentors as well. She was also going to need a distraction from her real purpose, since every good hero needs temptations to putter off in the direction of something shiny and forget the real quest.

I had a choice at that point when I was outlining the book. I could let the story play out— start it when Aurora was almost sixteen, and put Miriam in the place of Prince Charming to find some means of waking her sister once the curse had taken effect. Or I could twist the trope, and eliminate the Evil Fairy Queen right at the start, at the moment when she tries to cast the curse. I chose the second, because I wanted the spotlight to be unambiguously on the not-a-princess as the heroine of this tale.

Of course, that doesn’t mean I won’t do the first at some point, either. I still have a long way to go before I catch up with the number of books Isaac Asimov wrote in his lifetime.

From beloved fantasy author Mercedes Lackey comes a fresh and feminist reinterpretation of Sleeping Beauty.

Miriam may be the daughter of Queen Alethia of Tirendell, but she's not a princess. She's the child of Alethia and her previous husband, the King's Champion, who died fighting for the king, and she has no desire to rule. When her new baby sister Aurora, heir to the throne, is born, she's ecstatic. She adores the baby, who seems perfect in every way. But on the day of Aurora's christening, an uninvited Dark Fae arrives, prepared to curse her, and Miriam discovers she possesses impossible power.Soon, Miriam is charged with being trained in both magic and combat to act as chief protector to her sister. But shadowy threats are moving closer and closer to their kingdom, and Miriam's dark power may not be enough to save everyone she loves, let alone herself.